I arrived in Spain at the beginning of December for my seven-month Fulbright scholar award. For months, I had intended to include an update here. Ironically what I wanted to write was that the first month in Spain on the Fulbright award had enabled me to fully understand what a gift time can be. It’s rare to have that sort of support, as a writer: over half a year to focus and see one’s thinking evolve.

Of course, it turned out that I had far less time than I thought. The Fulbright Program was suspended on March 20th, as I’ve already written elsewhere: https://lareviewofbooks.org/short-takes/fulbright-covid-19/. I’m now back in the United States.

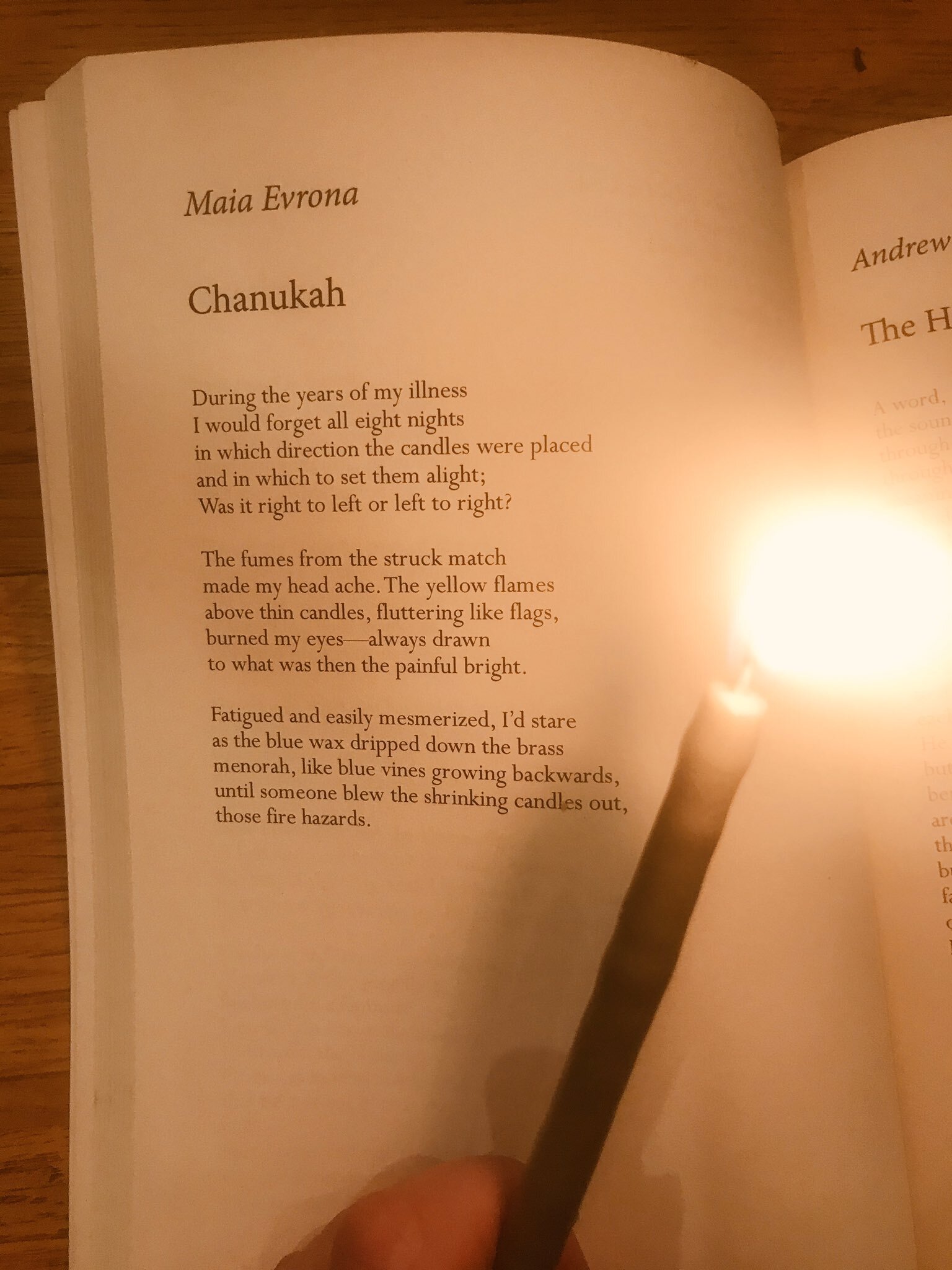

I don’t know that my Fulbright project will ever be finished in the way I expected, but perhaps writing projects never are finished in the way one expects. The interests and concerns that led me to apply for this award will remain, but the evacuation was disruptive, and I haven’t yet regained my train of thought. As a writer I’m in a privileged position compared to other scholars, because my main genre in past years has been poetry. Sometimes the poetic muse responds surprisingly well to disruption.

Still, I believed in the project I had intended to carry out. My goals included increasing Holocaust awareness in Spain and Greece, fostering better communication between the two countries and the wider Jewish world, and between Jewish communities themselves. I partnered with tiny cultural institutions that operate amid atmospheres that can at times be hostile.

Given my personal history and my status as a Jewish person whose work is steeped in Jewish history and the Holocaust, I have a healthy skepticism regarding authority and institutions, no matter how prestigious. While I was in Spain, I thought a great deal about how, while the Fulbright affirmation was nice, the most important element of the grant was simply having time and space to work, the freedom to make connections with others. What most moved me about the support from Fulbright was that the commissions in Spain and Greece had seen my work and wanted to support it, that my goals were goals they shared. I believe in the Fulbright Program’s mission of intercultural understanding, and took my role as a cultural diplomat for the United States seriously, particularly given that our cultural ties are currently strained. Through giving readings of my translations and highlighting their influence on my own writing, I thought of myself as a kind of ambassador for Yiddish poetry and looked forward, in the future, to being a different sort of ambassador for Spain and Greece.

It has been a strange time for me. I spent a decade—the formative years of my life—homebound due to illness. Watching the rest of the world shift onto that wavelength has brought up a number of conflicting feelings. I’ll admit to being annoyed by people complaining about isolation, considering the prolonged isolation I have known, and the indifference of the world at the time. On the other hand, I am aware that my concerns about my time in Europe being cut short may also seem trivial to others, though I believed in the work I was doing. The severity of my illness has given me a sense of living on borrowed time, of knowing that being sick once only makes it more likely that I will be so in the future, and that adds to my frustrations during this pandemic. Of course, this personal reality also added to my fears leaving Europe. We all have underlying life experience that may be brought out in ways others don’t quite understand during this time.

I hope that in the coming months I can tap into some of the research I did in Spain. The photo is from Mallorca, which I visited at the beginning of February. Mallorca has a remarkable but also heartbreaking Jewish history, and was perhaps the place I most appreciated seeing.

The day I arrived, I made an interesting personal discovery that superficially had nothing to do with Mallorca, though it was related to my formation as a poet, and thus what had resulted in my being there. My first published poem was included in the longlist of the inaugural Montreal International Poetry Prize, released as an e-book in 2011. I had mixed feelings at the time. I have hesitations about the ethics of charging poets entry fees and am turned off by the way the contest system ranks poems based on the subjective taste of judges. I’m often not impressed by the poems that win. I suspect that judges may feel pressured to choose long epics. I was surprised that my poem placed at all, as it was short and lyrical. The poem was inspired by the years I spent homebound, and the gift that literature could be at the time. It was also inspired by the Yiddish legend of the paper bridge, which says that when the Messiah comes, the righteous will go to the promised land on a bridge made out of paper, while the wicked will go to gehenna on a bridge made out of iron.

I’m sure that the influence of Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on a Wire” was also there. I was stunned to learn, via a promotional email for this year’s Montreal Prize, that Leonard Cohen himself was the anonymous donor who had funded that first Montreal Poetry Prize and thus was responsible for my first publication as a poet. Suddenly, a publication I had felt uncertain about, and which I have considered removing from my CV (it was only the longlist after all) became one that is perhaps closest to my heart.

Sometimes the future holds surprises about the present.